“The world forgetting, by the world forgot.”

Alexander Pope, “Eloisa to Abelard”

I was tired. For consecutive nights I had stayed up swiping left, swiping right, scrolling endlessly and feeling nothing. Everyone everywhere around me had found their match and yet there I was: a single man without a thesis to call his own.

“It’ll feel a bit like falling in love,” a peppy grad told me over drinks after another unsuccessful night out in the stacks. She examined the lack of inspiration her hopeful words had on me. I was thinking how falling in love was not something one usually planned for, and my thesis had a due date.

“Or like what that judge once said about obscenity,” she tried. “Either way, you’ll know it when you see it.”

Romantic or pornographic, I was ready for anything. I’d been in a slump since I started grad school and saw no hope on the horizon. I had become convinced, quite convinced, that everything that had ever been written had already been written about. That is, that the Conradian age of uncharted literary criticism was long gone, that without the chance to stake my career on the joys of literary discovery I would be forced to evolve into one of those critics that relish battles of interpretation, which did not bode well for me, a lack of competitive spirit being no small part of why one gets into the humanities in the first place.

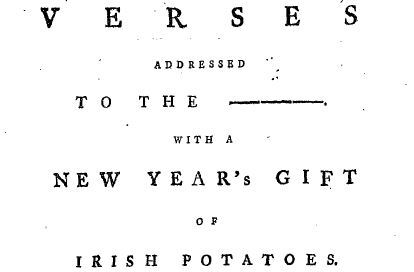

One night in the fall, however, everything changed. I was up late in the library–like only me and permanently jet-lagged exchange students late–and I was so deep up the ass of NYU’s digital archives that I was sure, sure no one had seen what I was seeing before. The text was from 1775 and was called “Verses Addressed to the — with a New Year’s Gift of Irish Potatoes.”1 It was on the 32nd or 33rd page of search results, on my 13th or 14th tab (NYU’s library search engine, like all university library search engines, gets so excited when you use it that it immediately ejaculates a new tab, which after a long night of shacking up in the stacks can lead to quite the progeny).

The curious title caught my eye. I lingered over it just long enough to read the even more anomalous name listed as the tract’s author:

LORD KNOWS WHO

I clicked. The title page informed me that it was an “Imitation of a Late Poem” and had a snarky bit of Latin written at the bottom: Clarior e tenebris. “I shine brighter in the dark.”

I looked around the dimly lit backrooms of the library, then leaned in closer. Despite its arcane 18th century style, the text bore a distinctly punkish spirit. I discovered that it was parody an earlier poem, “Verses Addressed to the Queen with a New Year’s Gift of Irish Manufacture,”2 a real sop piece written by a suck-up Anglo-Irish earl to his queen (“Could poor Irene gifts afford/Worthy the consort of her Lord…”). Pitted against the original, the Lord Knows Who poem sounded like the Sex Pistols. The mysterious author held nothing sacred. In “Verses Addressed to the —” they pan the King, the police, and the imperial project writ large. The aim in doing so is nothing less than mutinous.

“Theirs be the blame, who are the cause,

By making those strange things call’d laws,

That give the weaver’s fancy scope

In manufacturing–a rope.”

My little corner in the library suddenly turned into a delightful hermitage. Nobody else on earth was reading what I was reading. A strange, nearly forgotten sensation began to reshape inside me. Even though I understood zero of the historical context for which the poem was written, I felt an immediate kinship with the author. It wasn’t their political sensibilities so much as their sense of humor. Lord Knows Who. There was a streak of the modern in it. A pseudonym that doesn’t disguise its pseudonymity, touched with a nonsensical flair. It’s how I imagine future historians in 2400 might feel when they stumble upon dril’s twitter deep in the archival cloud. Even though the subject was hyperlocalized to its cultural context, the spirit of the thing, like all attraction, had echoed off my present in some inefficacious way. All I knew was that the program vet had been right. Whether it was love at first sight or erotic enchantment, I had known my thesis as soon as I had seen it.

A slight hyperbole requires correction: somebody in the 21st century had seen “Verses Addressed to the —” before me. Obviously. I did not stumble upon an actual book that had been stored away for centuries, its obscurity easily ascertained by the layers of dust built up on its bindings. There’s no dust on the internet, only metadata, and in this case its online viewership was unavailable. My judgement of Lord Knows Who’s inconspicuousness, then, was more instinctual than evidential, once again a case of knowing it when I see it. In any event, it was clear some archivist had considered the text important enough to be digitized and uploaded to Eighteenth Century Collections Online (ECCO), the academic database used for such research, and that therefore it wasn’t totally unspoken for.

There was one piece of evidence, however, to corroborate my instinctual judgment of the text’s relative obscurity. Most 18th century texts with pseudonymous authors have the author’s actual identity appended in a popout tab on ECCO’s website. “Verses Addressed to the —” did not. The only indication that someone had ever researched the piece was a hastily written hint scribbled at the top of the original manuscript, in actual ink rather than digital.

“R. Nugent (R.C.) Earl Nugent” This was the archivist’s code for Robert Craggs-Nugent, an Irish politician and earl who dallied in poetry throughout his life. It only took a quick bit of research to discover that Nugent had written the previously mentioned sop piece, “Verses Addressed to the Queen with a New Year’s Gift of Irish Manufacture,” that Lord Knows Who had parodied with “Verses Addressed to the — with a New Year’s Gift of Irish Potatoes.” However, this reference was the one and only lead my predecessor had left me. Their trail to Lord Knows Who ended with Nugent. So it’s with Nugent that we’ll begin.

We should take care not to treat Robert Craggs-Nugent as this post’s villain, even if he found himself in the crosshairs of our hero. Nugent is himself a terrific character who is more than welcome to grab a seat in the Arizona Room. Born in 1702 in Co. Westmeath, Nugent remained a lifelong Irishman despite his British peerage, serving alongside figures like Edmund Burke in the cause of favorable Irish trade relations.3 He gained fame from his poetry before his politics, publishing work in the humorous periodical The new foundling hospital for wit.4 (Aren’t the titles of these 18th century texts just terrific?)

This periodical, which was basically an 18th century version of McSweeney’s, was published by the same publisher of Lord Knows Who, a man named John Almon. This overlap immediately complicated things for me. Why would the same publisher put Nugent and his rival into print? My initial plan had been to search for Nugent’s most notorious political opponents and narrow them down by style to Lord Knows Who. Evidently, though, Nugent and Lord Knows Who weren’t politically polarized, otherwise they would never have found favor with the same publisher. Reading their respective poems closer, it became clear that the central disagreement between the two authors was more internecine than cross-aisle (it mainly had to do with levies Britain imposed against foreign ships trading with Ireland). It was therefore clear that Nugent’s satirist would not be an obvious political enemy, so I instead turned my attention to their mutual publisher to see if I could find any traces of Lord Knows Who among his other writers.

It’s here I began to feel a little weak at the knees. Not because of the sheer number of writers Almon published—in fact quite the opposite. I was feeling woozy because John Almon had published one author in particular, an author who had been at the center of one of the greatest literary manhunts in the history. An author who, like Lord Knows Who, had only ever been known by a single, mysterious pseudonym: Junius.

At this point I was in the middle of my first winter in New York City. I had finally quit restaurant work and started at an elementary school an hour and a half from my apartment. I traded late nights for early mornings. I got up at five, prayed for hot water, took the C to the A to the F with construction workers and nurses and snoozing transients, then humped it past the cetological carcass of the BQE down to the wind-spanked sitzfleisch of Red Hook.

All the while I was deep, deep in the shit with Lord Knows Who. I couldn’t be bothered when some dude on the downtown C dropped trou between cars before the break of dawn—my thoughts were lost in the eighteenth century. By this point I had already had several conversations with a professor who specialized in 18th century Irish literature and who hadn’t a clue as to the identity of Lord Knows Who. The burden of discovery was clearly on me. Literary critics rarely get to moonlight as Indiana Jones, but I was near days away from donning a beat brown fedora. (The scene in The Last Crusade when Indy slips out the window to avoid grading final papers and instead do field work in Venice is every academic’s wet dream.)

This sensation of grandeur was made all the more real by the addition of Junius. The Letters of Junius, published in 1772 and sold by John Almon, were a collection of 69 letters that were openly critical of King George III and his government. They were signed simply “Junius,” a reference to Lucius Junius Brutus, the founder of the Roman Republic who was credited with overthrowing the Roman monarchy. I have no problem saying that compared to Junius, Lord Knows Who is a small-fry. Lord Knows Who’s poem might have titillated the public; Junius’s letters absolutely bulldozered it. The letters caused such a stir in London that the only man traceable to their production, John Almon, was immediately put to trial and convicted of seditious libel. Rumors very quickly swirled about Junius’s actual identity. Notoriously polemical Whigs were interrogated (Edmund Burke: “I could not if I would, and I would not if I could”) but if anybody knew for certain they didn’t say. Theories about the identity of Junius ranged wildly, from Benjamin Franklin to Thomas Paine and William Pitt. It wasn’t until handwriting studies were undergone, first in 1871 by a handwriting expert then again in 1962 by a computer, that a strong suspect emerged: Sir Philip Francis.5

Could Francis be Lord Knows Who? Let’s examine the similarities. Francis was an Irish-born British politician and writer whose political sympathies align him closer to Lord Knows Who than Nugent. The Junius letters were written between 1768-1772, leaving plenty of space for Francis to recreate himself as Lord Knows Who in 1775. Perhaps most intriguing of all is that Francis’s father was a famous translator of Roman verse, which has a heavy influence in both “Verses Addressed to the —” and the Junius’ letters.

We were no longer talking “thesis” material here. Francis has never been verified as the author of the Junius letters. If in the course of searching for Lord Knows Who I could also verify the identity of Junius, I was not merely going to pass my m.a. program: I was potentially looking at academic stardom (more oxymorons to follow). I could have a celebrated dissertation, a stable academic job, even academia’s holy grail: tenure-track in my twenties.

I took my case to my professor. He patiently heard my ramshackle collection of evidence (at this point the tabs on my computer had begun to resemble the cm side of a ruler) before stating:

“Lord Knows Who is not Junius.”

(You can take my lack of response here as the onset of sudden catatonia.)

“I’m sorry,” he continued. “But Francis would not follow up a lampoon of the King of England with a pithy parody of some earl. He had much, much better things to do.”

And so did I, he seemed to imply. Another semester was coming to a close, which meant another round of term papers, and I couldn’t exactly slip out the window onto 5th avenue to avoid them. I sat despondent the whole train ride home, my daydreams of tenure replaced by the foreboding terror of adjuncting. Alas the Happy Isles of Ithaca! Curse the sinking gulfs of Stonybrook!

I had only one lead left to pursue. It was a longshot, but then so too was this whole literary treasure hunt to begin with. Besides, it’s not like I really had a choice. I was smitten with Lord Knows Who and couldn’t expect to be so lucky twice. I was willing to do anything not to give them up.

Next week…Part 2: Rich Widows, Poor Bastards, and the Case for Anonymity.

Alan Fearson, “The Identity of Junius.” https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1754-0208.1984.tb00089.x