An Obligatory Internet Article

Scrolling, Rambling, and What We Think of When We Think on the John

Listen, and you need to hear this: I didn’t start a Substack to write internet articles. Sometimes it feels like that’s all Substack was made for: writing articles about the internet. It’s already a stretch for me to be writing things on the internet, let alone on it in the philosophical sense. Besides, what does it even mean when we say an essay or a book is about the internet? It’s trendy in literary criticism to talk about the “internet novel,” or describe work as a “touching upon the condition of being extremely online.” For whatever reason critics (I suspect primarily middle aged ones) really bust a nut whenever someone structures their book like a PowerPoint presentation or Twitter feed (never mind the fact that Bishop Berkeley pulled off the latter approximately 400 years ago).

Yes, but, yet, however…the problem is that there’s one part of me that really is extremely online. That is, there is a certain part of my day that is wholly dedicated to the internet, consumed by it, in a way that feels natural but also historically unprecedented and therefore interesting for all the reasons that I tend to find anything interesting.

I’m talking about a morning scroll. Maybe you’re having one right now? I hope you’re enjoying it, and let me start by saying that yours is far more dignified than mine. Mine is shameless, aimless. I scroll in search of something to wake me up. These days the mornings in New York are quite dark. All the more reason to lay there letting my red eyes drip in the blue light, clicking on anything and everything: “Putin’s secret red button–it’s actually red”; “Luxe UES pad fetches $12 million”; “Best bags for women who travel”; “Why size did matter for neanderthals”; “Is Irish coffee actually…Scottish?”

It’s strange, this impulse I have to go on my phone first thing in the morning. It’s not that I wake up wanting to know the things I read on my scroll–that is, I don’t wake up with a desire to know Bryce Harper’s playoff OPS or the nine titles that should be on every biologists’ bookshelf. That would be bizarre. It is true that, per revelations in dreams, we may wake up with knowledge, such as when a dream of a snake consuming its own tail led the German chemist Auguste Kekulé to awake with a new understanding of the structure of benzene. But knowledge is hardly the concern here.

Information is whatever it is that draws my conscious mind to a morning scroll. By information I merely mean any text that can be read or image that can be seen while scrolling on my phone. The unconscious, insofar as I can tell, couldn’t give a shit about such information (do you scroll in your dreams?). Why my consciousness ever wants to scroll is difficult for me to understand. You might say it’s done to cope with the effects of “information overload,” which I have always understood implies a certain restlessness among the modern man. But is scrolling relaxing? Not really, otherwise every morning I’d fall back asleep. If anything scrolling distracts me from the fact that I am relaxed, which is probably closer to the reason why, at this point in my life, it is extremely difficult for me to wake up without a scroll.

If scrolling is not relaxing, though, then what is it? The best I can put it is that scrolling feels like not thinking–that is, it feels like whatever not thinking feels like. As Sam Kriss writes in his own Substack internet essay:

“Whenever I’m listlessly killing time online, there is nothing.”

Being nothing, I can only describe it by negation. Whatever it is I feel while scrolling is the opposite of Leopold Bloom’s mental state while he squats in his backyard outhouse in Ulysses, which, as my professor John Waters likes to say, marks the end of the “long constipation of English literature.” On his way out back Bloom grabs “an old number of Titbits,” the print equivalent to those inane SnapStories, which Bloom, no dull-wit himself, values for the occasion precisely because it will give him “something new and easy” to read. I think we’re all on the same page here. But watch what happens in Bloom’s mind while he reads, watch the interplay of information and thought that comprises his inner dialogue. I’m going to quote extensively here, but it’s Joyce so literally calm your titbits.

“Asquat on the cuckstool he folded out his paper, turning its pages over on his bare knees. Something new and easy. No great hurry. Keep it a bit. Our prize titbit: Matcham’s Masterstroke. Written by Mr. Philip Beaufoy, Playgoers’ Club, London. Payment at the rate of one guinea a column has been made to the writer. Three and a half. Three pounds three. Three pounds, thirteen and six. Quietly he read [...] It did not move him or touch him but it was something quick and neat. Print anything now. Silly season. He read on, seated calm above his own rising smell. Neat certainly. Matcham often thinks of the masterstroke by which he won the laughing witch who now. Begins and ends morally. Hand in hand. Smart. He glanced back through what he had read and, while feeling his water flow quietly, he envied kindly Mr. Beuafoy who had written it and received payment of three pounds, thirteen and six.”

Remember, when Ulysses was published it was hailed as a revelation in the stream-of-consciousness style. For its earliest readers the prose seemed like a transcription of exactly how one thinks. My question for you is this: do you think like this when you’re scrolling on the shitter? In Bloom’s mind thinking and information split the mental bill, whereas the feeling I get during a scroll is that the content on my screen comprises, at the time of scrolling, the sum total of my inner dialogue. I am just speaking phenomenologically. Again, we might be quick to point to “information overload” as the root cause of our inability to think while scrolling, but it’s not like we are any more bombarded by information when we scroll Apple news than we would be looking at an ad-infested copy of Titbits, or even standing in front of a Breughel painting or Walden pond. So what is it about information encountered while scrolling that creates the sensation of not-thinking?

Again, the instinct here is to blame information overload, and consequently to prescribe unplugging as the cure. There are worse things one can do than get off social media, but I don’t think (because I’m a case in point) that doing so eliminates the scroll. I’d even venture to say that disconnecting from the internet, period, would hardly keep you from scrolling. We’re so far past the inflection point of information overload that even a solar flare induced digipocalypse couldn’t save us from it.

Just as the internet is, conceptually, not unique to our time, information overload is hardly unique to the internet. Five hundred years ago a different technology introduced humankind to this predicament. Ironically, this technological invention is today often regarded as the panacea for our attention deficits. Like the internet, it so utterly transformed human society that even language (especially language) couldn’t escape its effects. You and I have likely never unwound a roll of parchment, yet everyday, thanks to the internet, we scroll. Likewise, folks of 16th century urban centers hardly ever found time for walking through the countryside, yet because of books not a day went by that they didn’t indulge in a mindless, shameless ramble.

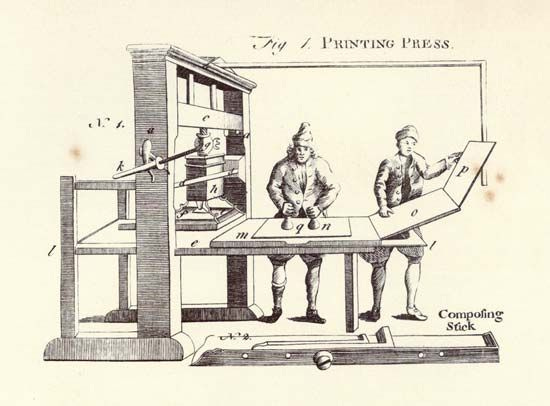

Like the internet, the printing press did not merely replicate old mediums of information with greater efficiency but created a new medium entirely: the book. Oh yes, we mustn’t hesitate in calling books a technology, anachronistic as it seems. We might be tempted to assume books have been with us since the first writer put their pen to the page, but we must take care not to confuse books and manuscripts. Manuscripts were handwritten, illustrated, and usually had the scribe’s name written at the end. Books were a good deal different. They had strange things like title pages and prefaces and footnotes and epilogues and dedications, all equally as foreign as the lockscreen and ringtone would have been in the 16th century. While the earliest books were simply printed versions of costly religious manuscripts–much like how the earliest stages of the internet simply delivered microforms of your newspaper–the printing industry soon began to manipulate the many possibilities of book technology to make their own books stand out amid the growing avalanche of content.

Much like the proliferation of websites on the internet, the rise in the number of printed books was meteoric. By the time our old friend Lord Knows Who picked up a pen in 1776, over one billion books had been printed in Europe. Let’s dwell on this billion number for a moment, because I think there’s an important similarity here with the history of the internet. In September 2014, Tim Berners-Lee, the inventor of the World Wide Web, tweeted that the internet officially hosted a billion websites. You remember 2014. Ice bucket challenges, Kim and Kanye’s wedding, Ben Affleck’s dong in Gone Girl. Like every year in the internet age, the success of each of these events was predicated on its malleability online, its capacity for virulence. This was nothing new. What was novel, however, was the way we started talking about such events. A successful piece of content no longer simply plagued the internet as viral. It went a step further–it broke the internet.

I’m not going to pretend that the phrase “broke the internet” was first uttered in 2014, but as an average online pedestrian I can pretty confidently report that the statement emerged (to quote Maud Lebowski) “in the parlance of our times'' in tandem with the revelation of Kim K’s caboose in the Winter 2014 edition of Paper. Of course, what we mean when we say that something broke the internet is not that we broke it but that it broke us. What the phrase seeks to capture is not so much the disintegration of the internet’s stratum as the human capacity to understand it.

While far from broken, the internet in 2014 was indeed showing signs of fragmentation, of being broken into smaller and smaller bits. Vine, the beloved, algorithmless predecessor for that purest product of the attention economy, TikTok, had just passed its peak number of users. Facebook was largely experiencing a demographic change as more parents, grandparents, and members of the Global South joined, whose low level of media literacy turned its landscape into something reminiscent of a hacked Modern Warfare I server. Meanwhile, internetgentsia emigres increasingly fled to Twitter, whose character caps eventually proved the ultimate reproof to Pascal’s famous dictum: “I have made this longer than usual because I have not had time to make it short.”

What’s the effect of this shift towards fragmentation? What happens to us, phenomenologically, when the internet increasingly presents itself in bits so rapidly digestible that they begin to resemble our own thoughts? There is little trouble understanding why corporations should desire that we engage with the internet in this way, but why do we so willingly oblige? The answer may have something to do with how humans have always reacted to information overload. It’s a trend that ought to concern us, all the more so because its harbinger is so obvious. We thought to celebrate, however momentary, the billion website mark. What we failed to do, however, was look at what happened when the printing press achieved the same milestone. If we do we can clearly see that it was only after passing the billion mark that books, like the internet, started to break.

To find the evidence of a broken print culture look no further than John Dunton, a relatively little known author of the early 17th/18th century whose life and work provide early warnings about the dangers of scrolling. Dunton is first and foremost a bookseller, being best known today for having created the first advice column in his paper The Athenian Mercury. This beloved question-and-answer supplement was made up of questions submitted by the public to be considered by a secret society of “Athenians,” which included poets, mathematicians, philosophers, and even some household names like Jonathan Swift and William Temple. Queries were as wide ranging as the anonymous public who submitted them, anything from “Were there any men before Adam?” to “How can a wife distinguish between her husband’s breeches and another man’s?”. Because the advice column was anonymous, theologically or culturally taboo topics could be considered and discussed openly. One can see the bubbling of the early spirit of the internet in these columns. They’re fun, they’re new, and their titillating effect is predicated on a sense of discovery.

I think it could be reasonably argued that Dunton invented modern social media with his advice column. As far as I know, The Athenian Mercury was the first public communications forum for the anonymous exchange of ideas. Anonymity, as I’ve written elsewhere, had already been a valuable means of communicating ideas in the 17th century. What Dunton recognized was anonymity’s value in creating a community.

There’s a whiff of paradox in this–how can you have a community where nobody knows each other’s names?--that ought to have served as a deterrent to its success. But a stringent standard of social politesse meant that people likely already felt a detachment from themselves in the public sphere, whereas the anonymity of the advice column offered a space where they could be their true selves. One can see this in the kinds of questions being posed to the journal, 30% of which, according to scholar Maureen Bell, were about gender issues.

I can’t be sure of this, but I suspect that Dunton feared the possibilities of liberation that his own journal could foster. It is otherwise hard to understand why he would shutter The Athenian Mercury’s open doors to repurpose his technology for a project that adhered closer to his own ideological convictions: The Night-Walker.

The Night-Walker, like The Athenian Mercury, was an anonymous forum for the discussion of public issues. Unlike the Mercury, it had a specific aim: the investigation and public prosecution of sex workers in London. The paper was composed of detailed reports submitted by nameless vigilantes who went on night missions to discover the whereabouts and whoabouts of prostitution. It’s sort of the perverse version of what we know to be true of new technology today: that its first application is almost always sexual. Which isn’t to say that The Night-Walker didn’t get some people off. For the kind of religious incel who actually likes the feeling of blue balls, its columns are positively pornographic. Here’s a tease:

“[A woman was] sent to offer her Company to a Gentleman who came in [the brothel] by Chance. [He asked] that she would carry him to a private room, but after she had showed him all the House, he told her there was never a room private enough to hide them from the eyes of God, and read her such a severe Lecture against her loose way of living.”

Got ‘em! With The Night-Walker, Dunton took his secret sauce of anonymous communities and slathered it all over a personal crusade. Dunton himself endorsed such puritanical views of sexuality and clearly had a kink for the voyeuristic pleasures offered by this prostitution proselytization business. In this way he is not too different from our own tech giants today, whose successive strings of projects reveal deeply rooted desires to simply be liked, loved, or fucked.

The Night Walker, however, does more than just anticipate Mark Zuckerburg’s need to create a new universe just to find friends. In a way, its following The Athenian Mercury anticipates the entire trajectory of the internet itself. To better see this, we ought to look at the alternate title for the publication, which like The Unexpected Virtue of Ignorance or The Evening Redness in the West serves as a better title than the first one listed. The Night Walker was also known as Evening Rambles in search after Lewd Women, a title which (I’ll pause for the laugh track) does something very peculiar with the English language. The word “rambles” evokes a very old tradition among English intellectuals, who often discovered their best thoughts on aimless strolls in the countryside. (In fact the leading walking charity in Britain today takes after the traditions, calling themselves “The Ramblers.”) A true ramble is playtime for the unconscious. You walk and think your thoughts, uninterrupted or unanticipated by what’s on a screen. It could very easily be argued that the same curious spirit infused The Athenian Mercury, but nobody in their right mind would refer to the whore-hunting missions of Dunton’s holy vigilantes as “rambles.” These were conscious assaults on personal freedom whose outcomes were determined before the abuser even stepped out his door.

The consequence of referring to this practice as “rambling,” then, is to exchange the domain of the unconscious for that of the conscious. That is, to replace a mode of thinking that is unfettered, associative, and pre-ideological with one that is restricted, monolithic, and deeply ideological. This replacement, however, doesn’t just happen in the linguistic sphere. In effect, a substitution of the unconscious for the conscious is exactly what happens in the social media sphere with the replacement of the Athenian Mercury with the Night Walker. The anonymous forum of public discussion no longer has any sense of randomness, of unpredictability–of humanity–but is instead a carefully choreographed discourse ultimately conducted for the sake of an ideological goal founded on inhumane principles.

It is my contention that the internet has suffered a similarly tragic replacement. 2014 might not be the exact moment that the unconscious internet was replaced by the conscious one, but by the time we hit one billion websites it had never been more clear that the internet had lost its ability to benefit public discourse. It is also my contention, however, that this timing is not accidental, and that it is not entirely our fault. If our first information overload engendered similar habits to our latest one, it may be that information overload makes us susceptible to the temptation of having our thinking done for us.

I don’t mean to jump immediately to technologies like the neurolink (though one of these days we’ll talk about it), but I think this desire not to think is at the heart of my scrolling moods. It is somehow easier, or maybe just less strenuous, to let an algorithm take care of my free associative thought. Rather than being an active decision, going on my phone in the morning feels like avoiding a decision. Maybe this is because even though my mind is never more primed for a true mental ramble than after waking, there is still some effort involved in letting it do so. It is this specific effort, to decide to think, that I believe was introduced by the printing press in the 15th century and has only become more difficult to accomplish with the internet.

Did it have to be this way? Justin E.H. Smith argues that the internet as a tele-communicative technology is inevitable in nature, but that what we’ve done with it is not. The internet is, at its best moments, still a beautiful place. The glory of Wikipedia, which Smith calls “this cosmic window I am perched up against, this microcosmic sliver of all things,” is tantamount to why the internet might be worth it after all. Plus there are websites that do their best to mitigate the scroll. Who knows: given the nostalgic benevolence we feel towards apps like tumblr and vine, we might even soon see social medias that brand themselves as “algorithmless,” the internet version of gluten-free. There are worse things.

My general hope is that one of humankind’s greatest capacities eventually frees us from the scroll: namely, that we become bored of it. This is maybe not so far-fetched a possibility as it may seem. Indeed, you and I have already seen how social medias come and go. Dunton himself is again a case in point. After Evening rambles in search of Lewd women he went on to create increasingly more insane projects1, concluding in the aptly titled Amazement of Future Ages, a massive compendium of mere information that in its rambling scope resembles the closest thing I can find to 17th century TikTok.

Something like intelligence won out in Dunton’s era. He died relatively penniless, his attention-economizing books losing in sales to critical works like Swift’s Tale of a Tub or Pope’s The Duncaid, which explicitly made fun of rambling culture. I’m not calling for a resurgence of the snarky intelligentsia online (though resuscitating Something Awful wouldn’t hurt) but something far less conventionally intellectual. All I’m asking, of myself first and foremost, is that we are once again able to take a shit like good old Leopold Bloom.

Of course, Bloom had a luxury that we haven’t. His old number of Titbits wasn’t also a necessary means of commerce, communication, and navigation. He could not, as we can, mistake time on the john for being business rather than pleasure. But there’s a subtle beauty to what he does with his own device once he’s finished with his morning scroll that we might begin to consider for ourselves: “He tore away half the prize story sharply and wiped himself with it.”

Let’s promise each other that, in ten years time, if none of this changes, we’ll do the same.

Well-spaced bullet points will be necessary here.

The art of living incognito: being a thousand letters on as many uncommon subjects, written by John Dunton during his retreat from the world, and sent to that honourable lady to whom he address'd his conversation in Ireland (1700)

The life and errors of John Dunton: late citizen of London; written by himself in solitude. With an idea of a new life; wherein is shewn how he'd think, speak, and act, might he live over his days again (1705)

Bumography: or, a touch at the lady's tails, being a lampoon (privately) dispers'd at Tunbridge-Wells, in the year 1707, Also, a merry elegy upon Mother Jefferies, the antient water-dipper. (1707)

Just finished this on the porcelain bus and can’t help but wish my iPhone was 2-ply. A great essay indeed, thanks for sharing.

Truly a great essay, man